Long ago a young man was charged to continue to push forward the mission of Jesus on an island in the Mediterranean Sea. The communities that Jesus established were to bring his message and manifest his Kingdom throughout the earth. This would happen as the Words of God were proclaimed faithfully and good works were done in his name.

In this introduction I want to orient us to the book of Titus and to some of the flow and setting surrounding this letter. In doing so, we will first look broadly at a category of writings in the New Testament now commonly referred to as the Pastoral Epistles. We will have a brief discussion of the authorship of these works and then move towards a focus on the settings and purposes of these New Testament letters. Next we will shift our focus to the person of Titus and the setting of his labors on the ancient Mediterranean island of Crete. We will then examine the work to which Titus was called and conclude with a challenge related to all of Jesus’ people, including the community of Jacob’s Well.

What follows is by no means an exhaustive discussion but I do hope and pray for a few things. First, I want us to grow in our trust and confidence in the teaching of the Bible. Second, I want us to learn to see ourselves through the lens and calling of a man like Titus working on the island of Crete. Finally, I pray that our study of Titus leads us to more fully embrace the call of God on our lives today.

Now, before we move to a discussion of the Pastoral Epistles I want to give a brief encouragement on how to read this paper. If issues of biblical scholarship are of interest to you, plow straight ahead. If you want to practically orient yourself with the main ideas associated with the book of Titus; jump forward in the paper to the header “The Book of Titus.” Now, let’s introduce ourselves to the Pastoral Epistles.

The Pastoral Epistles

The New Testament can be thought of as a small library of writings made up of various types of literature. It begins with the gospel narratives of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It continues with the second part of Luke’s writing, the book of Acts. This book lays out the early missionary efforts of Jesus’ followers as they took the gospel of Jesus throughout the known world of their time. Much of the rest of the New Testament is comprised of instructional letters to various churches and Christians written by apostles and early church leaders. The most looming author of these letters is the Apostle Paul.

Born Saul of Tarsus, this man was a prominent Jewish leader at the time of Jesus’ resurrection. He was raised a devout Jew, as a citizen of Rome in a city rife with Greek culture and learning. His life was a confluence of cultural worlds and viewpoints. At the outset of the book of Acts we find this man a fervent persecutor of Jesus’ followers seeking to put down what he felt was a heretic aberration on the Jewish faith. Then something happened; Jesus dropped some knowledge on Saul. Jesus radically changes Saul’s life direction by knocking him off his horse, telling him that he would now serve Jesus and on a mission to bring good news to the whole world. The Old Testament promises of God’s salvation for the Gentiles would be fulfilled through Jesus’ ministry through Saul (see Isaiah 42:1-9; Acts 13:47). This man would be known from that day forward as Paul the apostle, Jesus’ messenger to the Gentile world. From the early days of the Christian movement, Paul worked as a missionary taking the good news of Jesus’ death, burial and resurrection to people throughout the world. He would teach and preach the meaning of Jesus’ kingdom and work on the cross for sinners in various places, crossing geography and culture to do so.

Most of Paul’s letters were written to instruct new churches or groups of new churches certain areas of the ancient world. The letters usually dealt with theological and practical matters which emerged as people became followers of the new way in a city. The letters of 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus are slightly different nature in than most of Paul’s letters in that they come to us as personal correspondence from Paul to his younger ministry delegates.[1] Paul’s missionary work would move forward through community as their mission work was conducted in teams. In other words, Paul always had a posse as he worked in the mission of Jesus. Two of the most mentioned colleagues of Paul were the young bucks Timothy and Titus to whom the letters of 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus are addressed.

Up until the 18th century these letters were simply numbered among the Pauline corpus of literature and it was not until the works D.N. Berdot and P. Anton of Halle that they became known as “the Pastoral Epistles.”[2] The question of the authorship of the pastorals has become an interesting field of scholarship in the last few centuries so we will spend a bit of time with this topic as we continue.

Authorship

The letters now classified as the Pastoral Epistles were well known in the very earliest days of the Christian movement and were never questioned as to their inclusion in the canon of the New Testament. They find themselves listed fully in the Muratorian fragment as among the epistles of Paul.[3] Sections of these writings were mentioned as early as Polycarp (c.117)[4] and were in use by many of the early church fathers in the 2nd century including Irenaeus of Lyon (c.180) and Clement of Alexandria (150-215).[5] Though less certain and disputed, it is quite possible that 1 Clement and the writings of Ignatius of Antioch make reference to the pastorals in the late first century AD.[6] A few things are certain. First, the pastoral epistles were always thought to be the works of Paul written to his younger ministry apprentices. Second, this conviction was the long standing and unbroken tradition in the churches for over 1700 years.

Questions Arising in the Modern Era

In the 1800s several schools of biblical criticism arose through scholars on the European continent. Working under enlightenment assumptions, many began to question the teachings of the Bible and the teachings of Christianity. One of the past times of this flavor of scholarship has been to doubt the authorship of almost every New Testament book. Beginning with the works of German theologians F.C. Baur and Friedrich Schleiermacher, modernistic scholars did just this with the Pastoral Epistles. Paul’s letters to Timothy and Titus were now imagined to be works of fiction authored by some unknown pen in the 2nd century. True story; men of Germany, living close to 1800 years after the fact, sought to figure it all out for us and set the record straight regarding the Pastoral Epistles. Since that time, a growing consensus of doubt has been arrayed against the long held tradition that the author of these works was “Paul, a servant of God and an apostle of Jesus Christ” (Titus 1:1). Though there is an impressive list of scholars who question this skeptical position,[7] it remains the critical view in our time.

The Doubting of Paul

John Stott, in a popular level commentary, summarizes the critical position along historical, linguistic, theological and ethical lines.[8] First, the details of the pastorals are difficult to reconcile with the details we have of Paul’s travels and imprisonments in the book of Acts. Second, the vocabulary and style of these letters is rather divergent from other letters accepted as authentically Pauline. Third, the theology of these letters seems to be much more developed than the issues Paul is concerned with in earlier letters. Particularly of interest is the more developed view of the church and church leadership. Finally, the letters seem to encourage ethical conformity and keeping a good image in the broader culture. Some have even gone as far to say that the pastorals present a bourgeois Christianity, seeking only a good face and comfort in the world rather than Christ centered mission.[9]

There are many theories of authorship circling in New Testament studies today. First, there are those who still hold that the letters are outright forgeries and fictions. Others hold that fragments and traditions of Paul’s teachings made it into these compositions. These Pauline ideas were then compiled by an editor who used the common practice of attaching someone’s name, in this case Paul, to give the documents credibility in the churches. [10] This practice, known as pseudonymity, was employed by someone other than Paul in order to make the letters have more standing as they appeared in his name. Much more can be said here, but for our purposes we find these views to be highly problematic. What follows is a brief sketch of why we maintain that the apostle Paul is the originator of the Pastoral Epistles.

Reasons for Pauline Authorship

There are several reasons why those with a high view of the Scriptures maintain that the author of the Pastoral Epistles is the apostle Paul. The following is only representational of the arguments involved.

The Text of the Pastorals

The actual text of the pastorals is quite personal and makes several open claims which must be counted a spurious if we reject Pauline authorship. First of all, here are the opening greetings of each letter.

- 1 Timothy - 1Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by command of God our Savior and of Christ Jesus our hope, 2To Timothy, my true child in the faith: Grace, mercy, and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Lord.

- 2 Timothy - 1Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God according to the promise of the life that is in Christ Jesus, 2To Timothy, my beloved child: Grace, mercy, and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Lord.

- Titus - 1:1 1Paul, a servant of God and an apostle of Jesus Christ, for the sake of the faith of God's elect and their knowledge of the truth, which accords with godliness, 2 in hope of eternal life, which God, who never lies, promised before the ages began 3and at the proper time manifested in his word through the preaching with which I have been entrusted by the command of God our Savior; 4 To Titus, my true child in a common faith: Grace and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Savior.

Furthermore, extensive personal details and commands relating to context are involved in these letters. First, Titus is addressed with instructions about what his mission is to be ministering on the island of Crete. Second, Paul says on two occasions in 1 Timothy that he intends to visit him soon (1 Timothy 3:14, 4:13). Additionally, Paul speaks to Timothy about a myriad of personal issues including his calling into ministry, his age, his stomach problems and his family lineage. 2 Timothy is a deeply touching last letter from a mentor to a young leader that is full of references to persons by name.[11] To insinuate, as some have done[12], that these personal notes are all elaborate forgeries to carry on a deception a fiction does unnecessary violence to the heart of these letters. Those who understand the inspiration of the Scriptures as the Word of God find no reason to embrace such vain speculation.

Early Church Univocal and Acceptance Never in Question

Those closest to the persons and events of these letters were of one voice in their recognition of them being the work of the apostle Paul. Passing down the teaching of Jesus and the apostles was of utmost importance to the early Christians. We see this in all the New Testament documents and we see this in the writings of church leaders. There was never any doubt to the church that the Pastorals were Pauline and that they were inspired Scripture revealing to us the Word of God. Furthermore, it was not until the 19th century that German scholars, working under dubious assumptions and modernist epistemologies, that people began to question the authorship of the pastorals.

Problems with the Pseudonymous View

Much can be said about the practice known as pseudonymity in the ancient world. While it may have been practiced in the ancient world, the more relevant question relates to its acceptance by the early Christian churches. Far from accepting this practice, the early church vociferously rejected it. Consider the following as laid out by Ben Witherington III.[13]

First, when ancient writings were pseudonymous, they were almost always written in the name of an ancient figure far disconnected from the writing. In the case of the Pastorals we have documents that were written in the first century, just after the time of the death of Paul. Second, the letters are not generic teachings but are specific instructions of a personal nature to men living in certain contexts, namely Timothy in Ephesus and Titus in Crete. Witherington, quoting New Testament scholar I. Howard Marshall makes this point clearly.

As I. Howard Marshall has rightly stressed, it is one thing to write a book called 1 Enoch and use the name “Enoch,” but quite another to write a personal letter full of personalia and historical references and claim that it was written by someone in the recent past.[14]

Furthermore, we see that Paul himself rejected such pseudonymous practices (See 2 Thessalonians 2:2) and leaders in the early church rejected letters outright as well. The muratorian fragment, mentioned above, reflects this sentiment as it reads:

There is said to be another letter in Paul’s name to the Laodiceans, and another to the Alexandrines, [both] forgedin accordance with Marcion’s heresy, and many others which cannot be received in to the catholic church, since it is not fitting that poison should be mixed with honey.[15]

So though Pseudonymity may have been practiced by some authors in the ancient world it was never accepted to be anything but a farce and forgery by the early church.[16] The Pastoral Epistles were never thought to be anything but the work of Paul and the reasons for abandoning this view or far from conclusive.

No Compelling Reason to Reject Pauline Authorship

Above we saw that the reasons to reject Paul as the author followed historical, theological/ethical and linguistic lines. None of these are insoluble when we come to these writings.

First, it is quite possible to harmonize the historical details in these works with that of what we know from Paul’s other writings in the book of Acts.[17] Most would argue that the time frame of the pastorals requires Paul to be released from house arrest in Acts 28, travel perhaps briefly to Spain[18], then back through Crete and Macedonia where 1 Timothy and Titus pastorals were likely written in around AD 64-65. Finally, he would have been arrested and brought back to Rome as a prisoner under the persecution of Nero where he wrote his last letter 2 Timothy around AD 65-66. Tradition holds he was executed just after this, around AD 66-67, under the reign of Nero who died in AD 68.

Second, differences in theological focus make complete sense where the context demands it. Timothy and Titus were charged with establishing churches as the era of the apostles was closing. The mission of Jesus was continuing to move forward and the mission would need both true teaching and leadership after the apostles died. What we see during this time frame is just that. Letters were written to churches instructing them in the faith. The teachings and gospel narratives about Jesus were written down by the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The Pastoral Epistles provided clear instructions for selecting and empowering elder/overseers to pastor God’s churches and deacons to serve the needs of new communities. Elders and deacons were already mentioned by Paul in his letter to the Philippian church in as early as AD 62 so it is no surprise to see these offices given further form in Paul’s letters to young church leaders just a few years later. It makes sense that the task of ordering the early churches would have included some basic details about leadership, life as a community of faith and our relationship to the world. This is precisely what we find in the pastorals.

Third, differences in style and language can be understood in several ways. The influence of occasion and genre greatly affects both style and vocabulary.[19] What person today would use the same vocabulary and style to structure a logical theology treatise (like the book of Romans) and a letter to a dear from while writing from death row? Furthermore, there is a great deal of language that is common to the pastorals which is found in Paul’s other letters so the case is slanted in one direction by those arguing against the authorship of the apostle. When looking at the language and style of the pastorals one can see that the historical setting and subject matter demands different vocabulary to treat subjects relevant in the pastorals themselves.[20] Finally, in terms of the problem of style concerning the Greek of the pastorals, William D. Mounce makes a good observation:

If the Greek speaking church showed no sign of concern about how the PE [Pastoral Epistles] were written, one wonders why today the issue of style and vocabulary looms so large on the scholarly horizon.[21]

A final note about vocabulary is warranted. It is well know from Paul’s letters that he sometimes used a scribe, or an amanuensis, to write his letters and ideas down for him as he requested or dictated to them.[22] It is possible that the Pastoral Epistles were composed in this fashion. An interesting argument has be made by several scholars that Paul’s traveling companion Luke, who was called the beloved doctor, was the amanuensis employed with the pastorals.[23]

While some scholars today question the authenticity of Paul as the author of 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus, we find good explanations for their objections. The historical, theological/ethical and linguistic issues are not insurmountable and we remain convinced, with the long line of teachers and scholars in church history, that the author of Titus was indeed “Paul, a servant of God and an apostle of Jesus Christ.” With that in mind, let us briefly comment on some specific details regarding the book of Titus.

The Book of Titus

Setting and Dates

Following the chronology above, we believe Titus was written after Paul’s release from house arrest in Rome most likely from Macedonia. Paul and Titus had apparently been on the island of Crete sharing the gospel with people. The fruit of this evangelistic effort apparently needed to be cared for and set in order so Paul left Titus in Crete. We estimate the writing of 1 Timothy and Titus to be around 64-65 after his first imprisonment in AD 61-63.

Titus, the Man

From the records of the New Testament we find Titus to be one of Paul’s most trusted companions. Titus was a full Gentile and was an important link between the church’s Jewish origins and its future as one body with Gentiles together with Jewish followers of Jesus. In Acts 15 we find record of an early church council in Jerusalem where decisions were made regarding how much of the law of Moses the new Gentile Christians would be asked to keep. Paul and Barnabas met with the apostles at this council and Titus went along with them. Paul makes this a central point in his writing to the Galatian churches. He took Titus along and he was not required to be circumcised by Paul and the apostles. Titus, a young adult Gentile man, simply said – “Amen.” All the other adult male Gentile Christians also had a collective sigh of relief. Just sayin.

Titus must have had good peacemaking and conflict resolution skills as Paul dispatched him on two occasions to difficult church settings. First, he was sent to Corinth, where all matter of Christian crazy was going on in the first century (See 2 Corinthians 7, 8). Paul had all sorts of drama with the Corinthian church as his letters to them indicate. Titus was trusted by Paul to organize a collection for the poor and famine wracked Christians in Jerusalem from a church that had many tensions with the apostle. In Paul’s writing to this church, we find out that Titus was successful uniting people and collecting resources for those who were in need.

A few adjectives come to mind when reading about Titus’ role in the Bible.

- Courageous – He was saved from a pagan, Gentile background and stepped out in faith to full follow Jesus on his mission in the world.

- Loyal – He was with Paul and served at Paul’s request for many years.

- Humble – Every person charged with the difficult task of reconciling and calling people together on mission must be a humble person. Arrogance is like an explosive spark in tense situations.

- Submissive - Furthermore we see his humble submission to Paul by carrying out the apostle’s requests and serving as his delegate.

- Bold – Every person charged with the difficult task of reconciling and calling people together on mission must be a bold person. Passivity will let difficult people rule the day and create further conflict.

- Trustworthy – He was trusted by Paul with immense responsibilities in Crete.

- Responsible – Unlike many young men today, Titus was responsible enough to select leaders, refute false teaching, set households in gospel order and call mission forward in Crete.

- Compassionate – Titus had a heart for people that is exhibited by his love for the Corinthians, their trust in his character and the comfort he brought to Paul and his posse.

Crete – The Place of His Labors

The island of Crete is located in the Mediterranean Sea southeast of Greece. It is some 156 miles long from west to east and varies from approximately 8 to 35 miles in breadth. The island forms the southernmost boundary for the Aegean Sea.[24] The golden age of Crete was during the Minoan civilization which reached its heights in 2000-1500 BC. By the time of the New Testament Crete was of little influence in the classical world.[25] Crete is mentioned as part of the maritime shipwreck Paul endured on his way to Rome in Acts 27. Some have placed the writing of Titus to be around this time, but the evidence is unwarranted. More likely Paul and Titus engaged in mission on Crete after Paul’s first imprisonment where Titus was called to remain to work on church, household and mission on the island.

From the letter to Titus, we find that the Cretans were not a huggable, lovable bunch. In quoting a poet named Epimenides, Paul concurs that the Cretans are “are always liars, evil beasts, lazy gluttons.” So obviously Titus had his work cut out for him there. As an interesting aside, Paul’s quoting “of a Cretan” to say that Cretans are “always liars” has been used in an interesting logical puzzle know as the liars paradox. For if Epimenides told the “truth” then he is not always a liar. If he told the truth, he is also a liar. I think we know what Paul meant so we can leave that fun[26] for the philosophers and logicians for now.

From the letter we can see that false teaching was a problem on the island of Crete among those who had become Christians. The garden variety of Greco-Roman paganism would have been present on the island, but there were also those of Jewish background that were confusing the Christians. Apparently teachers were coming in trying to get paid for teaching their strains of esoteric monotheism. They are described as rebellious, empty talkers who were dividing households with their teaching. Not only this, they were constantly on the TV begging for money to do so. I’m sure they were a barrel of fun for Titus on Crete.

Titus’ Purpose and Calling

The purpose to which Titus is called on Crete is made clear by Paul in Titus 1:5 - This is why I left you in Crete, so that you might put what remained into order, and appoint elders in every town as I directed you. This instruction is congruent with Paul’s practice and pattern of ministry which we observe during his other missionary travels in the book of Acts. In Acts 14:21-23 we read the following:

21 When they had preached the gospel to that city and had made many disciples, they returned to Lystra and to Iconium and to Antioch, 22 strengthening the souls of the disciples, encouraging them to continue in the faith, and saying that through many tribulations we must enter the kingdom of God. 23 And when they had appointed elders for them in every church, with prayer and fasting they committed them to the Lord in whom they had believed.

It seems like Paul and Titus’ work on Crete was similar. They had preached the gospel and many had become followers of the risen Jesus. They had taught and strengthened the new disciples and appointed elders in the churches who would serve and lead under the Lord’s guidance. Today, many love to say that they are “spiritual” but do not like “organized religion.” Paul and Titus had a different perspective. They knew that godly servant leadership for new communities of faith was the plan and purpose of God. They knew that confusion and chaos can reign in people’s lives without men of character to serve and guide the people in good teaching and living out the faith together.

Paul knew that Jesus was going to use the church to make him known in the world. Jesus had commanded his followers to go and make disciples of all peoples and teach them everything he had commanded (See Matthew 28:18-20). The church, the community of Jesus people, is the instrument that God uses to manifest the gospel in the world. The book of Titus presents to us how we need to live as God’s people in the world in order for Jesus’ gospel to be manifest in and through us.

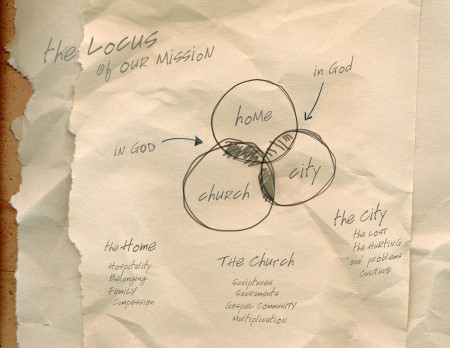

There are three spheres of life where the mission of God’s people overlaps. First, there is the church, the community of those who trust in Christ alone to be reconciled to God. As God rescues and saves people from sin, death and hell he adds them to his community called the church. Second, there is the household or family. We all live as members of some sort of household and this household can manifest or distort the gospel to others. Third, there is the broader culture and world in which we live and serve others. At Jacob’s Well we represent this with a simple diagram.

The book of Titus parallels these missional callings by giving us teaching on how we live together as the church and as families to manifest the gospel in our world.

- Manifest through the Church – Leaders and Doctrine (Titus 1) – Godly leaders, who serve under the Lordship of Christ and guidance of the Holy Spirit are to teach and refute false doctrine.

- Manifest in the House – Families Repping the Word of God (Titus 2) – Families are to live together in such a way that represents and not disfigures the beauty of the Word of God.

- Manifest Mission in the World – Gospel and Good Works (Titus 3) – We should live lives of gospel proclamation and gospel good works among others outside of the faith.

The Calling of Churches – Manifest the Gospel in Good News and Good Works

As we come to the book of Titus together I want Jacob’s Well to deeply wrestle with a few things which sound forth in this brief letter of just 46 verses and just over nine hundred words.

Proclamation of Good News

Some of the clearest articulations of the gospel are in this letter, clearly describing for us what God has done for us in Jesus Christ. I want us to see that there is always a gospel word manifest in the world through the faithful preaching of God’s people. Preaching is not simply standing up before people with the Bible in hand, though it certainly includes this. Preaching is declaring the gospel to people through explaining the gospel message in a way people can hear and understand. It may be done on trains, in offices, on airplanes, in coffee shops, in pubs, in homes and anywhere God has his people. The gospel is a message of God’s saving work in Jesus Christ that must always be shared with others. It must accompany a call to repent of sin and turn to Christ for forgiveness and a new life as his follower. I want Jacob’s Well to understand the gospel word better as we study the book of Titus.

A People United in Good Works

In addition to the words of the Gospel, Titus will teach us that we must also be a people who are eager to live lives of good works and service to others. A church that preaches a message it does not live is an offense to God and people we pray to reach with the gospel message. True faith in the risen Jesus will result in good works being the fruit of our lives. We are not saved, more loved by God, or forgiven in any way on account of the good works we do. We are saved by believing the gospel and trusting fully in Christ to save us. However, our relationship with God and our new life are demonstrated by what we do. It must be noted that a church that only does good works and looses the gospel message will be impotent to see lives truly changed, because it is the gospel that is the power of God to take guilty sinners and transform them by grace.

A Marriage Made in Heaven

As a pastor I have enjoyed the privilege of doing a great number of wedding ceremonies. One of the things I often share in concluding the ceremony is a quote from Jesus about marriage: What therefore God has joined together, let not man separate. (Mark 10:9) In reading the Bible I have come to the conclusion that God wants his people to be a gospel preaching community and a good works living community. However, many times God’s people separate that which God has joined together. Let me illustrate with two stories…two stories which are incomplete views of the “Christian Life.”

Two Incomplete Stories

Brian grew up in a church which would be categorized in the protestant tradition. He was taught to trust his Bible, believed in the death, burial and resurrection of Jesus for sinners like him. He believed in a God who would forgive all who accepted Jesus’ sacrifice on their behalf thereby making them free and forgiven by God. Brian graduated high school, then college, and then off to seminary in hopes of becoming a pastor. During this time he realized that Jesus talked a lot about caring for the poor.

Additionally, he started to change his belief that people needing have faith in Christ in order to be forgiven by God. There are many ways to god he imagined. Everyone is just good on their own…when they fail, God would just overlook it. If they wanted to worship things that were not God then God would understand. He thought the Bible was dated in light of modern knowledge and decided he would just follow parts of it which seemed right to him. As such he abandoned the cross as God’s judgment of sin and the means to forgive sinners and emptied the gospel of all New Testament meaning. He boiled down Jesus’ message to a simple statement: Do good for society, care about the poor, plead the causes of the oppressed.

What Brian has done is a tragedy, he has essentially denied the Christian faith into oblivion until what remains is but a social program which tells people to “be good.” No one is saved from sin, death and hell; the gospel has been emptied of its power and the cross has been marginalized. He is living a very incomplete story.

The second story is equally incomplete and tragic in its own way.

Susan grew up in an upper middle class family attending an Bible believing church in the suburbs. She embraced Jesus at a young age, but didn’t really understand it all until she began to struggle with an eating disorder in college. During this time she began to party and did some things she deeply regretted.

At this point a campus minister’s wife introduced her to Jesus; someone she thought she met as a six year old. She realized that God wasn’t just asking her to be good, because in ourselves we were not good.

She knew she needed forgiveness and grace from God and that this could not be earned by just being a good girl on Thursday nights. At this point in her life, she bowed a knee to the living Jesus and was saved by Him. She was very thankful, got involved in Bible study, and graduated with a degree in nursing. She married a doctor who grew up in church and loved Jesus and would turn out to be a good Daddy. They support campus ministry, attend church, live in an upper class gated community, have their children in the finest schools, they vote the right way and are generally nice people. Yet, she currently knows nobody who is not a Christian; she never associates with people of a different social class, and feels no need to do either. While her story may not be as tragic as Brian’s (or is it?) she is living an incomplete story with Jesus.

God desires for us to keep the gospel and good works together; it is a marriage that he has made in heaven. For Jacob’s Well to move forward as a gospel centered community we must keep this marriage intact. The gospel saves us, good works demonstrate the gospel and Jesus manifests his live and message through his community. It is my prayer that we might see this in the book of Titus. It is my prayer that we would be a people on mission, guiding by godly leadership, with households living in grace so that those around us would become followers of Jesus in our day.

Yours for the Glory of God and the Good of the City by extending hope through the gospel of Jesus Christ,

Reid S. Monaghan

NOTES

[1] Ben Witherington, A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Titus, 1-2 Timothy and 1-3 John, Letters and Homilies for Hellenized Christians (Nottingham, England, Downers Grove, Ill.: Apollos ; IVP Academic, 2006), 379.

[2] Donald Guthrie, The Pastoral Epistles : An Introduction and Commentary, 2nd ed., The Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (Leicester, England; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Inter-Varisity Press; Eerdmans, 1990), 17.

[3] The Muratorian Fragment or Canon is a description of the books accepted as authoritative Scripture around the close of the 2nd century AD. The relevant section to the pastorals reads “Moreover [Paul writes] one [letter] to Philemon, one to Titus and two to Timothy in love and affection; but they have been hallowed for the honour of the catholic [means universal] church in the regulation of ecclesiastical discipline. For a discussion of the Muratorian Canon see the excellent F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove, Ill.: Inter-Varsity Press, 1988), 158-169.

[4] Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles, The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown : An Introduction to the New Testament (Nashville, Tenn.: B & H Academic, 2009), 638.

[5] Philip H. Towner, The Letters to Timothy and Titus (Cambridge, U.K. ; Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2006), 4.

[6] D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 1992).

[7] Alfred Plummer, B. Weiss, Adolf Von Schlatter, Wilhelm Michaelis, Joachim Jermias, Ceslas Spicq, Gordon D. Fee, Donald Guthrie, Luke Timothy Johnson, J.N.D. Kelly, George W. Knight, William D. Mounce, Thomas C. Oden and Philip H. Towner and Ben Witherington III are among those who hold that Paul or one of his contemporaries serving as a scribe authored the Pastorals. List in Witherington, 51. I have concatenated Witherington’s name to his own list.

[8] John R. W. Stott, Guard the Truth : The Message of 1 Timothy and Titus : Includes Study Guide for Groups or Individuals, The Bible Speaks Today (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 23.

[9] Ibid., 23-28.

[10] For more on the modern objections to Pauline authorship see Towner, 15-26. And for even more detailed discussion see the introduction in William D. Mounce, Pastoral Epistles (Nashville: T. Nelson, 2000), lxxxiii-cxxix.

[11] Stott, 22.

[12] See Lewis R. Donelson, Pseudepigraphy and Ethical Argument in the Pastoral Epistles (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1986).

[13] Witherington, 62-64.

[14] Ibid., 63. For those who are needing some context for the quote, 1 Enoch is a writing that is named after an Old Testament character in Genesis five and is a compilation of works dated between 300-100 BC. It is not considered inspired, canonical Scripture by the Jews or by the majority of Christians (The Ethiopian Orthodox Church is the only exception)

[15] Bruce, 160.

[16] Köstenberger, Kellum, and Quarles, 640. An interesting story recounted by Tertullian (160-225) records a presbyter (elder) of a church in Asia being removed from office for trying to pass of a forged letter in Paul’s name.

[17] Witherington, 65-68.

[18] Paul states his desire to go to Spain in Romans 15 and a westward trip is referenced, but in no way historically certain, in the late first century letter of 1 Clement. Towner, 11.

[19] Ibid., 23.

[20] See excellent discussion of the literary issues involved with the pastorals in Mounce, xcix - cxviii.

[21] Ibid., cxvi.

[22] For example we see the book of Romans openly name the scribe in the following verse - I Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord – Romans 16:22.

[23] See Mounce, cxxvii - cxxix. and Witherington, 57-62.

[24] The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1988; 2002), s.v. "Crete."

[25] Ibid., s.v.

[26] See a fun little puzzle here for those interested - http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~cfs/305_html/Deduction/Liar%27sParadox.html

Bibliography

Bruce, F. F. The Canon of Scripture. Downers Grove, Ill.: Inter-Varsity Press, 1988.

Bush, F.W., The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids:Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1988; 2002.

Carson, D. A., Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 1992.

Donelson, Lewis R. Pseudepigraphy and Ethical Argument in the Pastoral Epistles. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1986.

Guthrie, Donald. The Pastoral Epistles : An Introduction and Commentary. 2nd ed. The Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. Leicester, England; Grand Rapids, Mich.: Inter-Varisity Press; Eerdmans, 1990.

Köstenberger, Andreas J., L. Scott Kellum, and Charles L. Quarles. The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown : An Introduction to the New Testament. Nashville, Tenn.: B & H Academic, 2009.

Mounce, William D. Pastoral Epistles. Nashville: T. Nelson, 2000.

Stott, John R. W. Guard the Truth : The Message of 1 Timothy and Titus : Includes Study Guide for Groups or Individuals The Bible Speaks Today. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1996.

Towner, Philip H. The Letters to Timothy and Titus. Cambridge, U.K. ; Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2006.

Witherington, Ben. A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on Titus, 1-2 Timothy and 1-3 John Letters and Homilies for Hellenized Christians. Nottingham, England, Downers Grove, Ill.: Apollos ; IVP Academic, 2006.